Margaret Cavendish 1623-1673

Born Margaret Lucas near Colchester to wealthy parents, maid of honour to Queen Henrietta Maria (wife of King Charles I), shy but an extrovert in attire and ambition – Margaret Cavendish was a pioneering polymath. She met her future husband, William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle, in Paris, whilst in hiding during the English Civil War. Enabled by her much elder husband’s financial and emotional support, Margaret wrote essays, plays, poetry, and fiction exploring gender inequality, marriage, science, animal rights, atomism and the natural world. She was a collector of microscopes and the first female to be invited to the Royal Society in 1667, whilst simultaneously engaging in public discourse with her male counterparts.

Her desire to be ‘singular’ manifested in remarkable means – by day she dressed in men’s clothing, by night she was seen wearing scarlet nipple tassels, her face littered with black velvet patches to hide her acne-scarred skin. She travelled in a solid silver coach with monochrome interior, reputedly pulled by eight white bulls. Margaret Cavendish used her celebrity to promote her extensive creative output in a male dominated arena.

In The Blazing World (1666), now considered a feminist proto science fiction novel, Margaret imagines a matriarchy run by an Empress based at the North Pole, her court mathematicians miniature lice-men. Robert Hooke’s 1665 Micrographia, and her own microscope experiments provided the source material. The strange novella was inspired by Christine de Pisan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) celebrating women, famous and unknown, historical and contemporary.

In Perihelia, Margaret Cavendish is re-imagined as Margaret the First, nominated leader of the matriarchy. Her key motifs in Perihelia are the louse, microscopes, white bulls and red tassels.

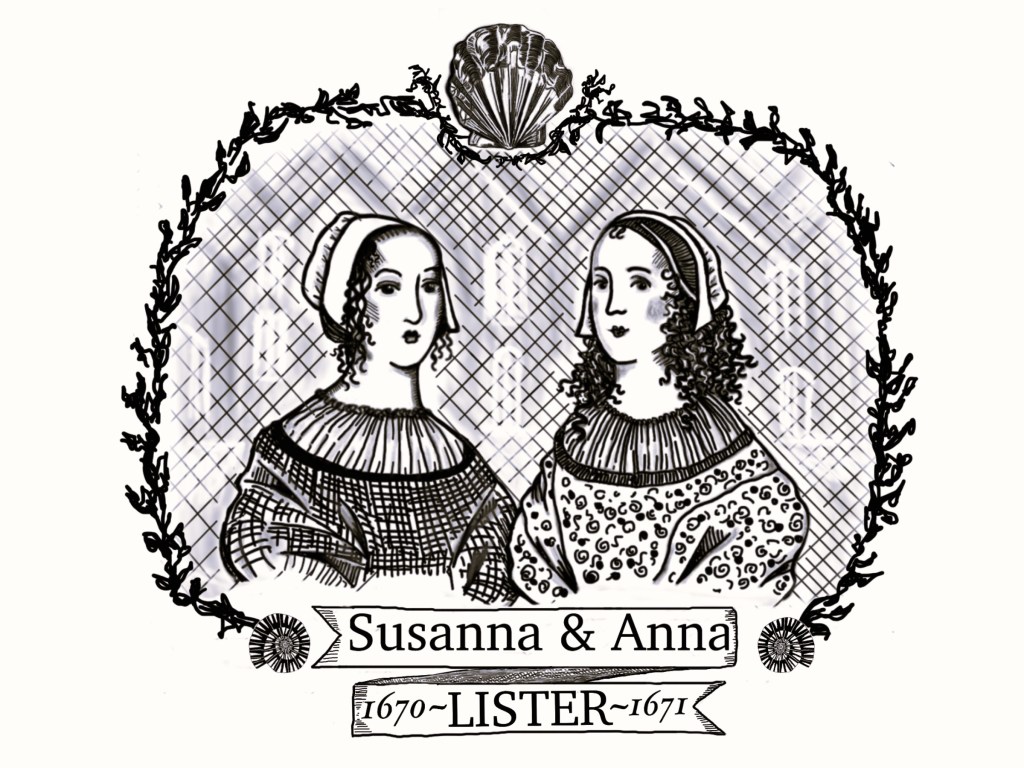

Susanna Lister 1670-1738 & Anna Lister 1671-1700

Accomplished natural history illustrators born in York, England. Sisters Susanna and Anna were taught to etch and then copper engrave at fifteen and thirteen years old. They created over one thousand illustrations of shells and molluscs for their naturlist father Martin Lister, for the magnus opus Historiae Conchyliorum (1685-1692). The younger sister Anna was the most prodigious illustrator and was said to be the first female to use microscopes for her illustrations.

Their key motifs for Perihelia are their shell engravings, the scribe’s hand, seaweed and their imagined likeness based on ancestral Lister women portraits.

Maria-Clara Eimmart 1676-1707

Self taught artist, engraver and astronomer in Nuremberg, Germany. Maria-Clara Eimmart predated the better known astronomer Caroline Herschel (b.1750) by almost eight decades. Her father taught her astronomy and together they self-built their observatory on the Nuremberg city walls.

Among some of her pastel and card illustrations are astonishingly accurate drawings of the moon, made from her telescope observations and included in her over 350 page illustrated volume Micrographia stellarum phases lunae ultra 300. Some of Eimmart’s comet and eclipse observations were dismissed at the time as false, as no male-led observatory had seen them, only to be proven accurate to the day by modern technology centuries later.

Maria-Clara Eimmart’s Perihelia motifs include the moon, comets, her blue and yellow pastel planet phase drawings, and an imagined portrait using Northern European late 17th century working woman’s attire, as we have no existing likeness of Eimmart herself.